Desectarianization and the End of Sectarianism?

By Simon Mabon

Desectarianization and the End of Sectarianism?

This report is the culmination of a year-long comparative research project on de-sectarianization in Iraq, Lebanon, and Bahrain. It uses both a most similar and most different methodological approach to produce detailed analysis of how sectarian identities play out in times of political contestation. On one hand, Lebanon’s and Iraq’s protest movements are two case studies similar in terms of how sectarian identities’ play out in the political and social fabric of states with power-sharing political models. On the other, Bahrain offers an important comparative insight due to the ways in which the ruling Al Khalifa family have co-opted, securitised then de-politicised sectarian identities.

It arrives at three over-arching findings: (1) desectarianization is a process that can take many forms, from the popular rejection of sectarian ordering such as that seen in Iraq and Lebanon to the state-led and ultimately elite-serving regulation of sectarian identities; (2) desectarianization manifests itself across our case studies in everyday dynamics that allow individuals to re-imagine social meanings; and (3) the process of desectarianization is neither inevitable nor linear. It is contingent on various political, social, and economic factors, not least the struggle of non-sectarian actors to overcome the episteme of sectarian politics and, subsequently, present a viable and organised alternative to sectarian orders. These findings are affirmed by numerous interviews with politicians, civil society activists, lawyers, human rights defenders, and academics from Bahrain, Iraq, and Lebanon. It brings together formal interviews and roundtable discussions to reflect on the intersectionality of questions about religious identity in political life.

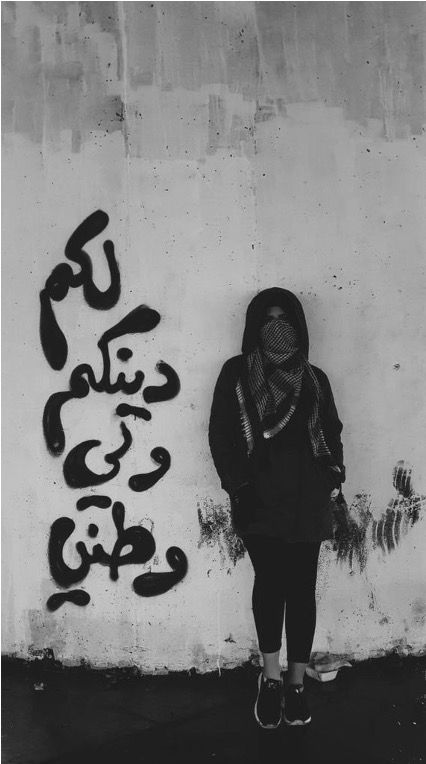

When zooming in on protest movements, the report suggests that the opposition to sectarian orders across its case studies are locked into a particular understanding of the political, defined exclusively by sectarian experiences, systems, and the very knowledge produced about such contexts. So, even when activists challenge the political system, they understand their act of resistance, in many instances, as “anti-politics”, given what “politics” entails in a strictly sectarian polity. In practice, protest movements are consciously avoiding the formal aspects of the ‘political’—political organisation and the pursuit of power—and consequently struggling to go beyond their sloganism and symbolic performances of resistance.

Many activists interviewed in this research project explicitly denounced violence in a follow-up to their rejection of party politics. This seems like a coherent position: why consider violence when these actors are not claiming to be an organised opposition challenging the status quo? Given the state of the opposition across our case studies, bottom up forms of desectarianization appear to be limited by the absence of political organisation, for actors who come together to speak the language of a power struggle. Accordingly, several questions remain at large: Can desectarianization exist as a political phenomenon without a struggle for power? In other words, is desectarianization an alternative order(s) to sectarianism? If so, how do/does this/these order(s) look like? And who, if any, is claiming ownership of these alternative orders? From this, what role does the state play in such processes? Is the state a target for actors involved in reimagining a non-sectarian order, or is it merely a constituent part of whatever order is in existence? And to what extent is the knowledge produced about sectarian systems able to help us understand the contestation of those identities.

Fundamentally, this report highlights that sectarianism and sectarian identities play a prominent role in the nature of the political in Bahrain, Lebanon and Iraq. While the essence of this differs across case studies, the salience of sectarian identities means that untangling or re-imagining their role in the political fabric of states – processes that are at the heart of desectarianization – verges on the existential, requiring engagement with all aspects of daily life from the political to the social, the economic to the production of knowledge.